WHY IS DISGUST DEPICTED IN ART?

- Kerry Lewis

- Aug 15, 2019

- 17 min read

A pursed or open mouth pulled down at the corners, a wrinkled nose and squinted eyes – the universal expression on disgust. Considered by many psychologists to be a ‘basic’ emotion, disgust alongside anger, fear, joy and sadness are pancultural, recognised by members of societies throughout the world (Korsmeyer 2011). At its core, disgust is a revulsion response to protect us from potential threats and dangers, but it rarely does so without capturing our attention. As McGinn states in his book The meaning of Disgust, ‘Disgust sticks in the memory and vivifies the senses, even when - especially when - it is deemed most repellent. Disgust is not boring […] the human psyche is drawn to the interesting and exceptional’ (McGinn 2016). It can cause an unsettling arousal, sometimes it is sad, sometimes funny, sometimes outrageous and naturally just plain revolting. Disgust requires sensory input, whether that be through smell, touch or vision, akin to an artistic setting such as an art gallery.

For many years artists have been regularly utilising the disgust response, whilst film makers have been developing ever more shocking special effects to repulse and nauseate audiences. Disgusting or shocking art is not a modern concept used purely by contemporary artists though. This is demonstrated in artworks such as Saturn Devouring His Son, by Peter Paul Rubens, dating back to 1636 and then again by Francisco de Goya Y Lucientes in 1821. Both depict the same Greek myth of the God who, fearing his son would take acquire his power, ate him. Of course, as Carolyn Korsmeyer notes ‘[…]it should not be forgotten that sometimes disgust plays its standard role of rejection; not all disgusting art can be savoured, nor for that matter valued.’ As also documented by Kant and Mendelssohn, once objects of disgust are portrayed in art, they must either trade-off aesthetic appreciation or be toned down to something merely ugly (Korsmeyer 2011). I believe this presence of aversion entangled with allure, calls for explanation.

Throughout this essay, I will explore ways in which artists have portrayed disgust in their work and for what recompense. How can the disgusting become interesting, comical and have us even savouring the experience? Initially, I will explore some of the main theories and concepts regarding disgust, such as its origins and role in moral protection. I will make reference to academics, including Korsmeyer and William Ian Miller as I examine the emotion in ideas such as, ‘the paradox of fiction’. From this platform, I will analyse the slogans of graphic designer Merel Witteman, which aim to give reason to the aversion and attraction phenomenon. Then I will look at Marc Quinn’s Self (1991), an artwork using his own body as material and decipher the reason for our visceral response. Moving on, I will also look at the work of Andrea Hasler, in particular, her installation Embrace the Base (2014). Through this, I will scrutinize whether disgust can enhance our engagement with art, specifically when a political message is involved. I will also analyse ways in which I have tried to express disgust in my own work and discuss how I hope my audience will engage with it. Finally, in my conclusion, I will summarise the concepts of my findings to reflect on the presence and value of disgust in Art.

If asked to think of something disgusting, what comes to mind? It is nigh on impossible to picture something that is non-organic or at least simulates the organic. Using McGinn’s example of a worn down, battered car that is peeling, rusty and leaking oil (McGinn 2016). It is significant, because man-made objects that share many of the same physical features of the disgusting, are not themselves disgusting – for example, things that are greasy, slimy, sticky, dirty, leaking, deformed, decaying etc.

Another strong component of disgust is the compromise of boundaries, as Korsmeyer puts it, ‘Aspects of the human body that operates at its margins, such as its orifices and fluids—holes and leakages that appear to compromise the intact, self-contained, clean body’ (Korsmeyer 2011). This is interesting as it acts as an indication of a deteriorating body. In Miller’s book, The Anatomy of Disgust he explains that our fundamental recoil stems from the recognition of our own mortality, that we will decompose and become the disgusting object ourselves. He argues that it is in fact decay that brings about life. Miller states ‘The having lived and the living unite to make up the organic world of generative rot … the gooey mud, the scummy pond are life soup … slimy, slippery, wiggling, teeming animal life generating spontaneously from putrefying vegetation’ (Miller 1998). This also rationalizes our fear of swarms, nests, hives, infestations as they symbolize the devolution to life-forms where discrete individual identity is insignificant. I believe McGuinn perfectly summaries disgust, by that which makes the body '[…] itself felt too much as a body' (McGuinn 2016).

It is impossible to talk about disgust without talking about the senses. We have been programmed to recoil from things that taste or smell foul, where contact or ingestion could prove dangerous. There are a number of disgust provoking substances that are similar across the globe - namely faeces, pus and blood. They can all bear diseases and parasites, but because it is difficult to determine exactly which ones are actually a potential threat, we have created a ‘protective umbrella’ (Korsmeyer 2011) of objects that elicit disgust that is greater than necessary. Therefore, what may be an irrational expression of disgust, is in fact, our mind protecting us from contamination. Such is the case with trypophobia (fear of clusters and holes), this may be due to the fact many diseases resemble holes or clusters on the skin. Of course, paradoxically often those foods held in highest regard like; cheese, cured meats and wine have been through a process of fermentation that comes with a foul smell. These luxurious delicacies still retain their link to the revolting as the decay accentuates and exaggerates flavours. Indeed, what is deemed as a delicacy by one society may be repulsive to those of another.

This supports the idea that this emotion has evolved by education and nurture. Disgust elicitors are culturally variant, but also produce such a visceral response. It is perplexing how the same sensory stimuli can evoke different responses from different audiences. To illustrate this point human adults are repulsed at the sign of faeces, whereas young children and animals appear unfazed. It should be noted that disgust arises in humans only at a certain age of cognitive development. As Korsmeyer states, ‘However, automatic and reactive the disgust response is, at least some of its activity requires a cultural account to understand’ (Korsmeyer 2011). I agree with Korsmeyer’s comment, but this means that often they are so embedded in beliefs and cultural values that we cannot say one side of the nature/nurture argument overrides the other.

Another theory is that ‘Disgust evolves culturally and develops from a system to protect the body from harm to a system to protect the soul from harm,’ says professor Paul Rozin (Rozin 1997). This view is that one of the prime functions of disgust is to keep us humans, at a psychologically healthy distance from our own animal nature. As Korsmeyer notes ‘[…] disgust is considered at one and the same time the most primitive of emotions, a modular response similar to the emotions that we share with other animals, yet it appears to be uniquely human’ (Korsmeyer 2011). With this perspective, we can control social boundaries and norms. On such a view, without disgust at violations of hygiene codes, lower animal orders such as vermin, perverse sexual activities etc. we would have been less successful in our evolutionary fight for survival. Whether those judgements should be trusted is a matter of controversy.

When disgust is depicted in art, the subject portrayed remains disgusting although perhaps to different degrees (a real-life encounter with vomit will always be more disgusting). It is the only emotion that cannot be transformed into aesthetic enjoyment when represented artistically (Kant as discussed by Korsmeyer 2011). This, and the fact disgust seems to present large barriers to make it actually pleasurable, makes it all the more complicated when trying to analyse the aversion and attraction paradigm. A sort of ‘anti-aesthetic’ is conceived, it requires a difficult cognitive assessment to try and formulate appreciation (Korsmeyer 2011).

The paradox of fiction is understood on the basis that ‘[…] emotions are sensitive to events of particular importance to the subject’ and that the rational mind understands if we are confronting an artistic rendition of something that poses no real threat to us (Korsmeyer 2011). Yet despite missing the belief in the imaginary subject, we still often respond in a visceral way with unpleasant recoil. What’s more confounding is that the main sensory triggers of the emotion are actually rarely depicted in art at all. Senses such as taste, smell and touch are often non-existent in a museum or gallery setting. In fact, art mostly provides us only with visual stimulation (occasionally audio), despite our physical body allowing us to encounter objects by various different senses. When a visual portrayal of a disgusting subject is experienced the mind is able to reflect. Whereas bodily senses of touch, smell and taste are immediate and reactive. It is the situation represented by a portrayal that we tend to find aversive rather than the mere representation itself, leaving the power of fiction in this scenario obsolete.

Graphic designer, Merel Witteman created a series of images for her 2014 Design Academy Eindhoven graduate project, Aversive Aesthetics which depicts disgust triggering photographs. Overlaid are quotes in a white slab capitalized font. The word ‘Aesthetic’ has roots in Greek, meaning ‘I experience’. Witteman has explored the idea of an effective aesthetic being one which generates an emotional experience. This correlates with my previous reference to Rozin, as it affects both the body and mind (Rozin 1997).

By using both text and imagery working together, the artworks grab your attention. One without the other would not have quite the same impact. The image would be universally recognized if stood alone, unlike the text which is only understood by English speakers. However, it would just be a purely disgusting image, that we may not even question the context of. This relationship is evidenced in the way the text has been placed on top of the image as if it is one. By not placing the text below or above the image it is clear they should not be separated. The text frames the scenario depicted and provides the viewer with a potential revelation to contemplate. Almost all of the text could be interchangeable with the various photographs, it is not image specific.

The images themselves are not extraordinary, mostly featuring everyday objects but in scenarios that instantly conjure up a repulsion reaction. A bare foot walking through faeces, snails climbing the side of a cup, they are often fairly relatable circumstances which make them all the more accessible to the audience. One piece reads the slogan, ‘Even when the shit is fake, the disgust is real’ (Fig 1. Witteman 2014). This plays on the paradox of fiction as described earlier, although they are actually fake scenarios, our emotional response is the same. Even if we have not encountered the exact scenario, we straight away recognise the object and are transported by our imagination into the experience. It is not the image itself that makes us recoil, it is the situation represented through it. This results in us curling our toes imaging a squelch sensation of walking in such a substance or pursing our lips at the idea of drinking from a slimy or contaminated cup. Or perhaps we cringe, laugh with unease or are amused with schadenfreude. I think this is partly due to the fact that humour and disgust share similar points of contact.

Witteman recognizes the power of disgust as a tool in design. The bold text in another image reads, ‘You’ll listen to interesting but remember disgusting’ (Fig 1. Witteman 2014). In an interview with Dezeen, she describes the changing role of a designer, now being more about telling stories and yet we are still using the same guidelines of the beautiful and clean (Dezeen 2014). It is clear to me, that Witteman recognizes although we may want to distance ourselves from the disgusting, we involuntary are also made curious and want to sneak another view. The format of the collection is also significant, rather than separate posters, it is displayed page by page in a book. I envision this as a sort of ‘coffee table book’, the kind you may display and dip in and out of for entertainment, instead of dedicating time to intently read. This maintains the concept of disgust actually being of aesthetic value, even amusement, not just something to be avoided at all costs.

Her work is interesting to me as she is stepping back and making people recognise this aversion vs attraction phenomenon, and just how bizarre, we as humans are. It is hard to disagree with any of her statements, she truly has managed to harness the power of disgust in her design work. This particular awareness is not something I have seen many other graphic designers delve in to, therefore setting her apart from the crowd. There is an interesting realisation from becoming conscious of the fact, that everything we’ve been taught about only things which are aesthetically pleasing or beautiful make ‘good’ design, is in truth false.

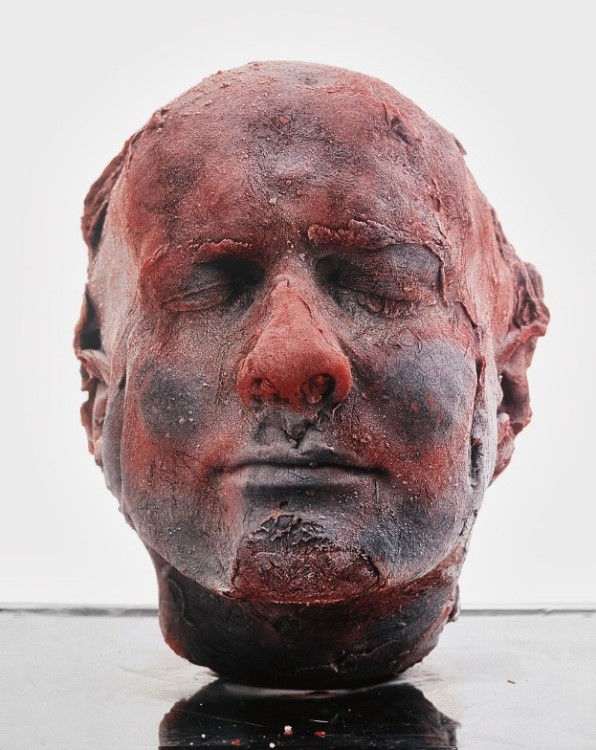

An altogether different representation of disgust in art is Marc Quinn’s very literal self-portrait (Fig 2.). Self (1991), directly uses the artist’s body as material, as he took a cast of his own head, immersed it in frozen silicone and poured in ten pints of his own blood, collected over several weeks. It is contained in a transparent cube that is kept refrigerated. Ice crystals slowly form, foreshadowing its eventual decomposition. Cultural History and Aesthetics professor Peter de Bolla, characterises an audience’s reaction to the work: ‘I have come across viewers who, on seeing Self for the first time, describe a sensation akin to tingling, a kind of spinal over-excitation, or a curious shudder – that involuntary somatic spasm referred to in common speech by the phrase “someone walking on one’s grave” (Bolla as referenced to by Korsmeyer 2011).

During the time of its creation the artist was an alcoholic. The work characterises the dependency of subjects needing to be ‘plugged in’ or connected to something to survive. The artwork relies on electricity to preserve its form (Korsmeyer 2011). Marc Quinn was part of the influential group of visual artists, known as The Young British Artists, who gained a lot of press coverage throughout the 1990’s. They are associated with much controversy for using shock tactics to draw a reaction from an audience. During this time the more obscure, disturbing and offensive art was, the bigger the potential for it to be praised for its originality. Work like Quinn’s, depends on spectators to be shocked, made uncomfortable and unsettled. This kind of ‘shock art’ responds to the public’s hunger to be challenged and a culture of sensationalism (Widewalls 2015). This connects with Sensation, the controversial 1997 Exhibition, which featured Quinn’s work alongside other members of the YBA. Self, takes a taboo subject, in this case, alcoholism and deals with it in an inappropriate way, a defining mark of ‘shock art’.

On first view, we may feel both intrigued and confused by the realism of the head. Then on knowledge of its organic material, we may feel disgust’s signature response of nausea. We may even have to ask ourselves difficult questions in order to detect the source of our disturbance, as the response is so instinctive. But why do I involuntary recoil in repulsion?

Although the notion of what disturbs us has been changing throughout history, to quote Contesi, ‘Becoming one with the worm’ (Contesi 2015) has been a constant distinction. Quinn’s Self, very literally projects our ‘fears about death onto the face of life’ (Henderson Ladybeard 2018). As discussed previously whilst referencing Korsmeyer, it is the illustration of a body with compromised boundaries that we find unsettling. The very medium of Self, the artist’s blood, suggests a boundary has been broken and health is no longer contained. The head without-body reiterates this interpretation, as it is a form that shouldn’t exist, the intimate contact of the viewer results in a feeling of unease.

I find it also interesting to note the non-existence of the paradox of fiction in this scenario. We are aware that this may not be an actual decapitated head, but it is made directly made from blood, organic matter from the body. So, it could be argued that this piece is not merely a rendition of a subject, but it actually is the subject. We are reminded of the sinister inevitability of our own ‘fairness so easily being reduced to foulness’ (Miller 1998). “Fairness” being our intact, healthy attractive bodies, and “foulness” being that which is repulsive and vile.

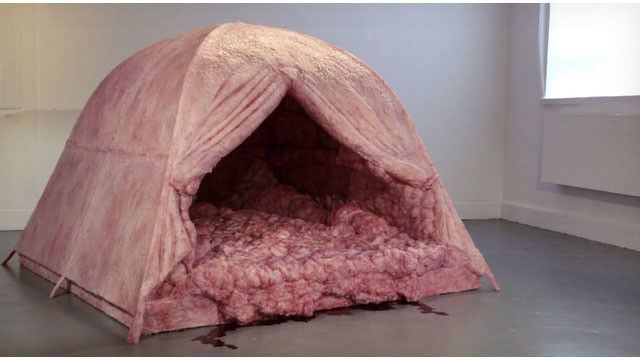

Provocative Artist Andrea Hasler exploits our involuntary revulsion in yet another form. Embrace the Base (Fig. 3), is a collection of pieces influenced by the female demonstrators, who in the early 1980’s protested against the nuclear weapons being kept at Greenham Common, Berkshire. The to-scale pieces were initially formed in fibreglass and then coated in wax to look skin-like. Hasler explains, ‘Metaphorically, I am taking the notion of the tents which were on site during the women’s peace camp, as the container for emotions and ‘humanise’ these elements to create emotional surfaces’ (Designboom 2014). These unconventional tents portray the ones used to house the protestors, albeit with a distinctively human, flesh-like appearance. These pieces maintain the structure of the tent, whilst also suggesting the consequences of nuclear war through faux intestine textures.

I believe Hasler is firmly aware of the very nature of disgust being rooted in sensory experiences. Mindful of the political and social context of the protest, she has been able to harness the power of disgust to demand an audience. Unlike Wittemans work, which has an air of humour, these objects feel much more sombre. Hasler has used the uncompromising emotion of disgust to give voice to her political statement. The scale and uneasy physicality of the objects command attention.

I believe a piece like this does not need a cultural encounter to understand, as I had quoted Korsmeyer argument previously. Even without the context, we recognise it relates to some form of violence or injury, the destruction of the intact and whole body. Again, I recoil instinctively, despite knowing this is art, a rendition of something rather than an actual object in life. Yet I, as a viewer question its surreal presence; was it once living flesh, how can this form exist? I find it interesting to consider the response of the viewer if the tents were two-dimensional paintings rather than three-dimensional works. When talking about her work Hasler says, ‘It’s interesting how people are often repulsed by the abject quality of a sculpture but can’t help themselves but to touch it’ (Hasler via WeHeartIt 2012). I certainly agree with this statement, this kind of uncomfortable viewing is rather ashamedly, compelling. People want to explore things physically, despite its uncertain outcome. Therefore, if this particular piece was merely portrayed on paper, I don’t think its effect would be to the same degree.

Hasler’s work has a rebellious streak and is familiar with dissecting the moral values and concepts we deal with on a daily basis. Another of her works feature a series of fleshy forms, manipulated and labelled to look like designer handbags. Again, Hasler is commenting on how objects can shift back and forth between being desirable and yet repulsive. I feel this statement on consumerism explores the idea that beauty is simply not just the opposite of disgust. In fact, I speculate that another source of disgust can be pleasure itself – a result of too much sweetness (Korsmeyer 2011).

The tantalising allure of disgust is something I have been exploring in my own practice. Led by my own fascination I have been examining the emotion on a tactile level. Using trypophobia, the fear of clusters, namely holes, as a starting point I have been questioning, why is it that in some people they can induce sweating, nausea and panic, whilst in others an irresistible curiosity. Often, we cannot help but poke and prod something we are disgusted by, but also instinctively enticed to explore its strange sensation. As Robert Solomon eloquently describes this in Savouring Disgust ‘Emotions are subjective engagements with the world’ (Robert Solomon 2011). Disgust helps us position ourselves in the world. I believe it is this fascination of the known and the unknown that appeals to our primitive nature.

I realised early on, to explore this relationship with the material world of disgust, my piece needed to be worn on the body. The contact with the wearer, but also, its onlookers are the prime focus of my work. By creating a garment that effectively swallows the body, I am looking at the correlation of the inside and the outside, what is visible and what is contained.

I have encountered the various problem-solving, that comes with trying to create something disgusting from non-organic materials. The organic being intrinsic to that which makes the disgusting, disgusting. This informed my decision making when choosing fabrics. Eventually, I decided on various fleshy hues as a colour palette, to hint at the skin of living matter. Scuba lends itself well to this, as it is smooth with a slight sheen. To create clusters of holes reminiscent of those which trigger trypophobia, I laser cut the scuba with hand drawn un-ordered circles to give a feeling of chaos.

After discussing with my peers what it is exactly about holes that makes them feel uncomfortable, the feedback was that it is the possibility something might be in, or living in the holes. This is consistent with Miller’s thoughts on the fear of devolution to infestations and creatures that swarm where individual identity is lost and the creation of ‘life soup’ (Miller 1998). Using shibori fabric manipulation, I have managed to create worm-like forms protruding from the holes. The only part of the wearer visible from the outside are the legs, making them faceless and without identity, which also plays on this. By using biomorphic, irregular shapes and silhouette of the garment, again I am hinting at the organic nature of disgust elicitors. As with the synthetic hair sprouting from the piece, this gives the impression of it being an unknown living creature.

I have also felted balls to be beaded and to sit inside of the holes. These look a little like eyeballs or the frogspawn carried under the skin of a Surinam toad, in the hope of provoking a skin crawling sensation from the viewer. This in combination with intestine like soft sculpture, give the impression of an impossible creature. Portraying specific organic subjects just enough to be recognisable, but in an abstract way, I am aiming to combine things that shouldn’t exist in one form.

If I have determined one thing from analysing disgust’s presence in art, it is that it is extraordinarily hard to articulate. I have found myself often asking myself, ‘But why am I having such a strong repulsion response, what is it that is actually disgusting? It is so ingrained in our thought process and instincts through both nature and nurture, that to really dissect it is a challenging task. However, I can conclude that with such a diverse variety of manifestations, no single answer will explain all cases of encountering disgust in art. I believe that the diversity of its forms demonstrates how complicated this emotion can be.

I have predominantly looked at disgust’s representations in visual forms. I could take this further by expanding my investigation into the other senses also. This would also be an intriguing element to explore through my own practice, to perhaps go alongside the physical, tactile presentation of my work.

Through Witteman's work, where the viewer is at just a far enough distance of safety that the disgusting is not too disgusting and may be amusing, we can understand how it may even enhance our experience. Quinn’s Self, leaves me questioning how it’s perceptions will change with time, in an age where we are much more aware of the daily trauma’s experienced across the world. Is it possible that we may become immune to shock and controversy, and with the over-saturation of ‘shock art’, it will eventually become less engaging and even expected? We have mostly come past the point of being outraged by the presence of a urinal in an art gallery, and yet the future looks bleak if these pieces become normal and loose their power in opening up conversations. On the other hand, the subject of disgust in pieces such as Hasler’s, still command our attention and have power in addressing political issues. Involuntarily, we find ourselves doing ‘double takes’ at the things that disgust us.

As discussed, utilising the power of disgust through art is no new concept. It panders to our search for that which makes us ‘feel something’. Paradoxically being faced with our own mortality as much of the disgust elicitors do, we are made to feel alive through adrenaline or as Bolla phrases a ‘somatic spasm’ (Bolla as referenced to by Korsmeyer 2011). The visual arts allow space for the contradictions that come with being human, the tension between the aversive and the attractive.

Plato said that the allure of disgust panders to an underside of human nature that ought to be quashed (Plato as discussed by Korsmeyer 2011). I speculate that we are all mildly perverted, at least possibly or in some scenarios. But when our curiosity arouses such an odd feeling of satisfaction, can we be to blame? I am confident that, that which is aversive, repulsive and disgusting in art, is here to stay.

Bibliography

Artnet.com. (n.d.). Marc Quinn | artnet. [online] Available at: http://www.artnet.com/artists/marc-quinn/ [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Brinkema, E. (2014). The Forms of the Affects. [ebook] The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=jWSSAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT186&lpg=PT186&dq=attraction+disgust+paradox&source=bl&ots=45iFI1GXwt&sig=ACfU3U2ms3cbqPTBv9MR_BbHDCTIkdLTCQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjWjMaip6LgAhXgTxUIHVH1DdQQ6AEwA3oECAYQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=true [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Contesi, F. (2016). The Meanings of Disgusting Art. Essays in Philosophy, [online] 17(1), pp.68-94. Available at: https://philpapers.org/archive/CONTMO-13.pdf [Accessed 28 Apr. 2019].

Contesi, F. (2015). Korsmeyer on Fiction and Disgust. The British Journal of Aesthetics, [online] 55(1), pp.109-116. Available at: https://philarchive.org/archive/CONKOFv1 [Accessed 17 Apr. 2019].

Dacic, A. (2015). Has Shock Art Become an Obsolete Term in the 21st Century? [online] Widewalls. Available at: https://www.widewalls.ch/shock-art-21-century/ [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Davidson, J. (2012). Talking repulsion and wax breasts with uncompromising Swiss artist.... [online] We Heart. Available at: https://www.we-heart.com/2012/04/11/andrea-hasler/ [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Designboom | architecture & design magazine. (n.d.). fleshy intestine tents by Andrea Hasler recognize nuclear consequences. [online] Available at: https://www.designboom.com/art/fleshy-intestine-tents-by-andrea-hasler-recognize-nuclear-consequences-02-17-2014/

E. Henderson, G. (2018). A Timeline of Ugliness. Ladybeard, (3).

Howarth, D. (2014). Aversive Aesthetics photos are designed to trigger disgust. [online] Dezeen. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2014/11/06/merel-witteman-aversive-aesthetics-photos-trigger-disgust/amp/ [Accessed 10 April. 2019].

Korsmeyer, C. (2011). Savoring disgust. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Martinigue, E. (2016). Disturbing Art - The Ingenuity of the Disgusting. [online] Widewalls. Available at: https://www.widewalls.ch/disgusting-art-grotesque-art/ [Accessed 1 May 2019].

McGinn, C. (2016). The Meaning of Disgust. [ebook] Oxford University Press. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8C1P4xUqa8UC&pg=PT38&dq=attraction+disgust+parado&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjh2Jjqst7hAhW4URUIHSeTDVAQ6AEIQjAE#v=onepage&q=attraction%20disgust%20paradox&f=false [Accessed 19 Apr. 2019].

Miller, W. (1998). The Anatomy of Disgust. 6th ed. Harvard University Press.

Sas.upenn.edu. (1997). Food for Thought: Paul Rozin's Research and Teaching at Penn. [online] Available at: https://www.sas.upenn.edu/sasalum/newsltr/fall97/rozin.html [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Comments